With an Eye Toward Development

As Land Use Professionals Offer Guidance, Expertise and Admiration, Designing High Schoolers Devise Plans for Fictional Blighted Area

By Alec MacGillis

Washington Post Staff Writer

Sunday, June 11, 2006; C01

The students at Fairfax County's Robinson High School, tasked with creating a redevelopment plan for a mock neighborhood, were stumped. Where could they put office towers without upsetting neighbors? How could they meet the city's demands for affordable housing, yet still make money?

Luckily, they had an expert standing at their shoulders to lend advice: Patrick Saavedra, part of the development team that is building MetroWest, a controversial high-rise project near the Vienna Metro station. Now the students knew what developers experience every day, he told them.

"You're going through the same things we go through," Saavedra said. "These things can take four, five years."

Saavedra's visit was part of an unusual initiative in the Washington area: Local developers are going to high schools in Fairfax, Montgomery and Arlington counties to advise students on land use issues as the students compete over several weeks to produce redevelopment plans for a fictional blighted area. The program is the creation of the District-based Urban Land Institute, a national research and networking organization for developers, architects and planners.

For developers, the program, dubbed Urban Plan, is a chance to counter stereotypes of themselves as rapacious interlopers and to discuss land use in a setting other than the often-tense zoning meetings where they usually encounter the public. Getting to interact with the next generation of potential neighborhood critics -- and potential clients -- doesn't hurt either, said Saavedra, an architect with the Lessard Group of Vienna, which designed the 2,250-home MetroWest project.

"If you have students get engaged early in these ideas . . . they'll understand that density does make sense in certain places. They'll appreciate these things as adults much easier," he said. "It's people being misinformed that makes them reject proposals. They've haven't gone through an exercise like this."

The organizers of Urban Plan are aware that having developers in the classroom could raise hackles in a region so conflicted over growth, and they insist that the program is motivated by more than wanting to smooth the way for future projects. At its heart, they say, is a desire to get young people to think more about the "built environment" in which they live, to understand what trade-offs go into shaping it and to realize that they can have a say in what it looks like.

"The last thing we want is parents saying, 'You're trying to force pro-development [views] down our children's throats,' " said Meghan Welsch, an Urban Land staffer who coordinates the program in the Washington area. "It's really not about that. It's a civic engagement lesson, to create a more elevated level of discourse."

Urban Plan started five years ago in high schools in California, where it was designed by the institute and researchers at the University of California. It has since spread across the country, to New York, Atlanta and Chicago, among other places. It debuted in the Washington area three years ago in Arlington, and this school year it was used in a total of 13 classrooms: at Robinson, Arlington's Washington-Lee High School and Bethesda-Chevy Chase High School.

The institute, which has about 100 developer volunteers enlisted, hopes to recruit more so that it can expand into additional schools, including some in the District.

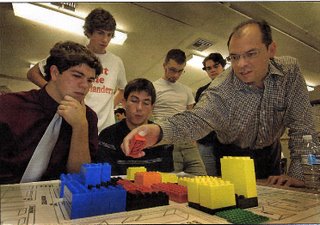

The sessions don't have overt markings of indoctrination. Government or economics teachers interested in Urban Plan spend several classes introducing students to the redevelopment project's guidelines, which include financial constraints and community demands. Students then break into five-person development teams, with each member assuming a role such as financial analyst or city liaison, and they then use Legos and laptop computers to produce a redesign for the blighted "Elmwood" neighborhood.

Students must decide how best to mix housing, shops, offices, parks and parking, while attaining a profit of at least 15 percent. Challenges include deciding whether to keep a homeless shelter or pay $1 million to move it off-site, whether to include a big-box store and whether to raze run-down historic buildings. Developers visit the classrooms to advise students and then, on the final day, serve as a "city council" to select a winner.

Watching high school students wrestle with some of the same questions as they do fascinates some developers. In an Advanced Placement government class at Washington-Lee, Jay Parker, whose firm designed the mixed-use Market Common complex in Clarendon, commiserated with students about the difficulty of incorporating adequate parking into their plans and later raved about the students' insights.

"When they started talking about 'absorption rates,' I was just swept away," he said, referring to the rate at which properties can be leased or sold. "I've worked with planning commissions that have less background than they do."

The developers also marvel at how much the students' plans are shaped by their own environment. At inner-suburban schools such as Washington-Lee and Bethesda-Chevy Chase, students are more likely to create mixed-use developments modeled on urbanized areas in their midst, such as Ballston. At farther-out Robinson, near George Mason University, students are more likely to include a big-box store such as Target, prioritize auto access and segregate housing from commercial development.

For all their interest in the project, however, most students interviewed said they had little interest in getting into the development business. Washington-Lee senior Emily Huston joked that she wouldn't be able to make necessary compromises on plans "because I develop really strong opinions, and I'd just want it my way."

But the students said they appreciated learning more about how development happens, particularly since they are surrounded by so much of it. "We have so much firsthand experience with [development], and now we get to apply what we've seen," said Chris Borer, a senior in an AP government class at Robinson.

And the students had no illusions about potential benefits to developers. "They know we'll be customers in the future, and they'll be appealing to us," said one of Borer's team partners, Chris Hill. "They're focusing on us now because they'll need us later."

When it came time for their final presentations last week, the students played the parts of developers convincingly -- many dressed up for the occasion, and they responded deftly to tough questions from the "councilors."

Challenged by Andrew Rosenberger of Madison Homes about the unusually high profit margins sought by his group, Hill said with a straight face that his team was taking extra profits so that it could cover any cost overruns that might arise later. "We don't want that money coming from the city," he said. "We want it to come from us."

It was a brazen answer, but it worked: The council picked his team's plan, which, in this case, meant not millions in profit but $25 bookstore gift certificates for each member of the team.

No comments:

Post a Comment